Here are a few things that should be demanded of anyone who is responsible in the health system.

As the editor of an international text on sexual harassment in medicine, I’ve learned a few things about doctors’ health.

I also have a few decades of experience mentoring, treating and working with doctors who are struggling.

I’ve just spent a day at a meeting discussing the psychosocial health of doctors. At the meeting, we saw an impressive framework, comprehensive documents and a lot of focus on large organisations.

However, it seemed to me that we failed to respect the role of power in maintaining poor behaviour at the top of the health edifice. There are good reasons why young doctors are overworked and underpaid, and it has nothing to do with their individual skills, capacities or resilience.

I used to love the book Everything I ever needed to know I learned in Kindergarten by Robert Fulgham. He has a way of reducing things to their essence. He talks about the “simple rules” we learn at kindy, which are in fact “the distillation of all the hard-won, field-tested working standards of the human enterprise”.

So here is my take on some of the things Fulgham describes. This is what we should demand of everyone who is responsible for the healthcare system.

Don’t hurt people

Teaching by humiliation is not on, and neither is humiliating others to make yourself seem more important. Stop arguing, stop criticising each other in public and for goodness’ sake, make sure any romantic relationships you have with colleagues are consensual. And none of this senior-to-junior-relationships nonsense. It’s just not on.

There has been too much nastiness, and it’s not helpful. Stop the insults. No more “clinical marshmallows”. No saying GPs are “twits”. How on earth does an intern feel safe if the leaders of the health system are so, well, rude? If you can’t say something nice about health workers, don’t say anything at all.

Clean up your own mess

I was listening to the discussion about psychosocial safety today, and GPs were mentioned twice. GPs were there to look after the students’ health needs and provide GP terms to help residents detox from lousy hospital culture. The rest of the time they were invisible.

Hospitals, health departments and other large institutions don’t get to shove the trauma they inflict down the garbage chute to the GP swamp. It is not our job to sweep up when the parade of hospitalists have created an unholy mess. We have enough emotional labour to manage as it is.

I am exceedingly happy to see medical students, and doctors in training. But don’t see me as the solution to psychosocial safety throughout the entire health system.

Play fair

If you’re a leader, manager or policy maker, don’t bite off more than someone else can chew. There is a nasty tendency to make sweeping announcements of new, shiny, services before shattering public trust by delivering an understaffed, under-resourced pale shadow of the promised nirvana. It just means the politicians get the praise while the clinicians cope with the blame.

The public and the media eviscerate clinicians who fail to live up to an impossible standard, and I wonder whether this is the point. By promising the impossible, the politicians get to be magnanimous to the voters, and can scapegoat the professions, implying their failure to deliver is due to a lack of education, motivation or moral fibre.

Shoving more into the GP curriculum, announcing a new item number or implying that GPs have an attitude problem (I’m looking at you, Ged Kearney, with your “medical misogyny” bandwagon) is a nasty strategy. Be fair. Don’t promise something you won’t resource.

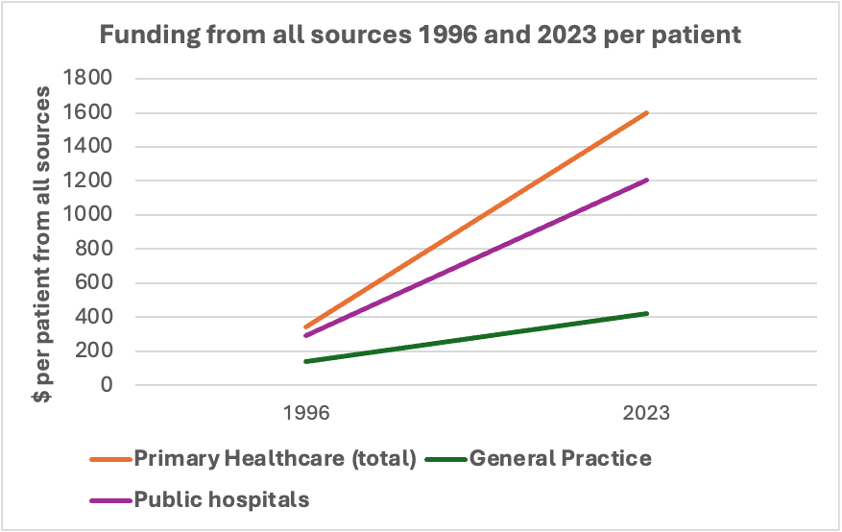

And for general practice? Don’t promise bulk-billing GPs and then reduce our resources, reallocating our budget and the more lucrative jobs to others. That’s just nasty. Here’s the data to explain exactly how nasty.

Don’t take things that aren’t yours

Don’t redirect money, from, say, public psychiatry and redirect it to appease the lobbyists in other areas.

There is only so much money to go around, and it is a government’s responsibility to allocate this as fairly as possible. Playing favourites with taxpayer money is wrong.

We all know a celebrity with a common, visible disease like breast cancer will drive all sorts of philanthropic and government investment. However, diseases that are invisible, embarrassing, stigmatised or rare, like ulcerative colitis, hepatitis or anal cancer will struggle to get appropriate funding.

I was reminded of this when I realised the falling-down weatherboard building that housed a truly world-class respiratory team at my medical school was razed to make way for the cancer centre car park.

To give you an even better example. My PhD looked at medically unexplained symptoms. Trust me, there will never be an invisible ribbon day or a fun run for people with medically unexplained symptoms.

It’s all a problem of prestige.

High-prestige diseases get more funding. People who treat high-prestige diseases with high-prestige technologies are well supported and well paid (think neurosurgery for brain cancer).

People who treat low-prestige, low-technology chaos (think general practice) are overworked, underpaid and undervalued. And while some are celebrated for their procedural skill, others are undervalued for hands-on caring, which to me is a gross misunderstanding of the skills required for both.

Overworked, undervalued teams are not psychosocially well. After decades of underappreciation, some eventually become quite nasty.

So, how about someone has the guts to stop overconsumption of resources for the rich and privileged, and redistribute resources on a more equitable basis?

Share

Professionalism is all about trust: as professionals we should increase (not decrease) trust in our profession. Good doctors, who communicate well, are competent, and make sure they respect all comers increase trust. Lousy communicators with terrible skills and biased attitudes clearly decrease trust.

So, shouldn’t we all share the benefits AND the responsibility of the system? Shouldn’t we all be accountable?

Bluntly, should there be an AHPRA for politicians, bureaucrats and managers who reduce trust in healthcare by overpromising and underdelivering? It causes harm, not only to the doctors, but also to the public who receive substandard care from burned out, overworked, disillusioned and depressed clinicians.

Stop it. It’s not fair.

Tell the truth

If “the way we do things around here” is clearly different to written policies, fix the policies. Otherwise, you are just lying.

When you go out into the world, watch out for traffic, hold hands and stick together

Stand up for your colleagues. Be an upstander, not a bystander. If necessary, take a leaf out of the book of the psychiatrists, and walk away from systemic abuse.

And while we are at it, don’t tell me some fancy new digital product “is what consumers want” if every single consumer you’ve spoken to is a well-educated, well-resourced, white Australian. I have never yet been in a committee with a consumer who can’t read. It’s time we optimised the system for the people who really need it. I bet the system would become simpler and easier to navigate.

So, stand up for your own rights, and for those who have no voice.

Live a balanced life

Learn some and think some and draw and paint and sing and dance and play and work every day some.

There is still a role for self-care. It is just not the antidote to systemic abuse.

Be aware of wonder

I think I have the best job in the world. When I lose that perspective, as I definitely did last week, I take my rage into the garden and bury it. Rage and frustration and bitterness destroys my health and my effectiveness.

When I go back to the coalface, into my consulting room, I meet people I deeply respect. There I find the purpose, meaning and wonder in the privilege of care, and I recharge.

Thinking of patients, including doctor-patients, gives me the strength to stand up against systemic abuse. It gives me the courage I saw in the NSW psychiatrists.

Doctors deserve better than the disdain and disrespect that has become commonplace in our health system. It is my hope that the seniors in the system defend that right for our junior colleagues, who are much more vulnerable to bullying, harassment, scapegoating, overwork and disrespect. We are the only ones with the power to defend them, and they deserve better.

So, for those of us who get to be “in the room where it happens”, expect kindness, and hold everyone accountable for demonstrating it, in their words, their policies and their behaviour. Otherwise, we are part of the system where the most junior, and the least privileged are deeply vulnerable. And that is unacceptable.

Associate Professor Louise Stone is a working GP who researches the social foundations of medicine in the ANU Medical School. She tweets @GPswampwarrior.