Nobody wants to miss a melanoma. But excessive caution brings burdens as well as benefits.

Our inability to tolerate even a single instance of failure by doctors is an important cultural driver in the continuing overdiagnosis of melanoma in situ in Australia, according to a leading epidemiologist.

Professor David Whiteman, senior scientist and cancer control group leader at QIMR Berghofer in Brisbane, told Dermatology Republic that overdiagnosis of melanoma in situ was “a fact of life”.

“Overdiagnosis is like gravity – it’s no good if you’re falling out a window, but it’s good for a lot of other reasons,” he said.

“It just exists and is a feature of any program of systematic screening or surveillance.

“In epidemiological terms, in the case of melanoma, overdiagnosis is the detection of a lesion that meets all the criteria – it looks like and feels like melanoma, but doesn’t display the biological behaviour of progressing to the point where it can cause death.”

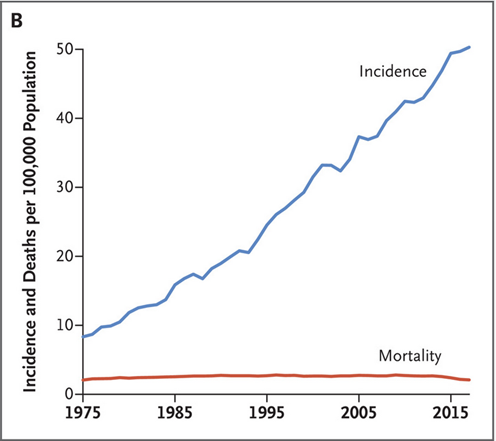

Speaking at the Australasian Melanoma Conference in Brisbane last weekend, Professor Whiteman and other presenters referred to a graph published by Welch et al. in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2021, showing the incidence of melanoma in situ versus mortality rate over time:

“You can interpret that graph two ways,” Professor Whiteman told Dermatology Republic.

“If we had not diagnosed those cases then the mortality rate would have gone up. That’s the optimistic view – that we have prevented many deaths.

“The other view is that finding all those cases has not decreased the mortality rate, so perhaps we could have done nothing to those lesions.

“Both of those things are going on, but we still see a rise in lethal melanomas [given the growth and ageing of the population].”

The clinical reality for skin cancer GPs, dermatologists and dermatopathologists is that nobody wants to miss even one potentially lethal melanoma.

“We can’t change our advice because nobody has the acuity to predict the future biological behaviour of a lesion on the skin,” said Professor Whiteman.

“At least we can’t do it to the level that would offset the threat of a lawsuit if we get it wrong.

“If we had a more tolerant system, we would watch and wait more often, particularly in elderly patients, for example.

“But the reality is the system does not tolerate a single instance of failure, and that is an important cultural driver of overdiagnosis – apart from the fact that nobody wants our patients to suffer.”

A prominent practising GP told Dermatology Republic that missing a melanoma was “one of the top three things that keep me awake at night”, suggesting that clinicians will continue to err on the side of caution when it comes to treating melanoma in situ aggressively.

One of the downsides of overdiagnosis is the financial strain on the Australian healthcare system.

Associate Professor Louisa Gordon, a health economist from QIMR Berghofer, told conference delegates that skin cancer was the most expensive cancer in terms of financial burden on the Australian health care system, costing approximately $1.8 billion per year. Melanomas contribute about $259 million per annum to that cost.

“These costs are increasing,” she said. “We’ve got this ageing population. Baby boomers are now elderly and coming into the healthcare system in big numbers – they are the most common age group for treating skin cancers.

“But we’ve also got Gen X coming through. These are people born in the [1960s and 70s] who are now in their 50s and 60s. There are eight million Australians in that generation who are about to come on to the healthcare system with skin cancers.

“We’ve got this greater awareness of the need for skin checks and we’ve also got a lot of new technologies on the horizon. All of these things are going to contribute to higher costs for skin cancer in Australia.”

But the financial burden is not the only consequence of overdiagnosis, according to Professor Whiteman.

“Patients diagnosed with early melanomas can experience psychological harms,” he told Dermatology Republic.

“They can become anxious, they may avoid going outside, perhaps they may withdraw from friends, family and social situations as a result. In some cases they may struggle to get insurance, or they may need to change jobs.

“Diagnosis is not without consequences, and right now we don’t have a good handle on the relative burdens of those consequences.

“We need to learn more about the biology of these lesions. We need to better harness the new technologies and the new pathology techniques to help us diagnose these lesions more accurately. It’s over to the research now.”