Prescribing immune checkpoint inhibitors to all cancer patients could lower the likelihood of future skin cancer.

The results of a small Australian study suggest immune checkpoint inhibitors can reduce the number actinic keratoses, a precursor for skin cancer.

Actinic keratoses are a precursor for cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas, and the risk of developing a cSCC increases by up to 20% when patients have over 20 actinic keratoses, reflecting field cancerisation.

Consequently, identifying therapies that reduce the burden of cSCC and other types of keratinocyte carcinomas is of great importance. Previous research has shown immune checkpoint inhibitors improve survival outcomes in people with keratinocyte carcinomas, but less is known about whether ICI can prevent new carcinomas from developing.

Now, a new Australian pilot study suggests that including ICIs in the treatment of any kind of cancer significantly reduced the number of actinic keratoses observed on patients. The findings were published in JAMA Dermatology,

“These results suggest that ICIs may provide benefit for field cancerisation as an immunopreventive strategy in high-risk populations,” the Brisbane-based research team wrote.

Researchers recruited 23 immunocompetent adults with at least six actinic keratoses on their bilateral forearms who were starting at least six months of treatment for any cancer that included a programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) or programmed cell death ligand (PDL-1). Nineteen patients remained alive and enrolled in the study at the 12-month follow-up.

Three-quarters of patients were male and the average age of patients in the prospective cohort study was 70 years. Two-thirds of patients received monotherapy with an anti-PD-1 antibody, with the remainder receiving a combination of anti-PD-1 and anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 antibodies. The most commonly prescribed ICI regimen was a nivolumab/ipilimumab combination therapy, followed by nivolumab alone.

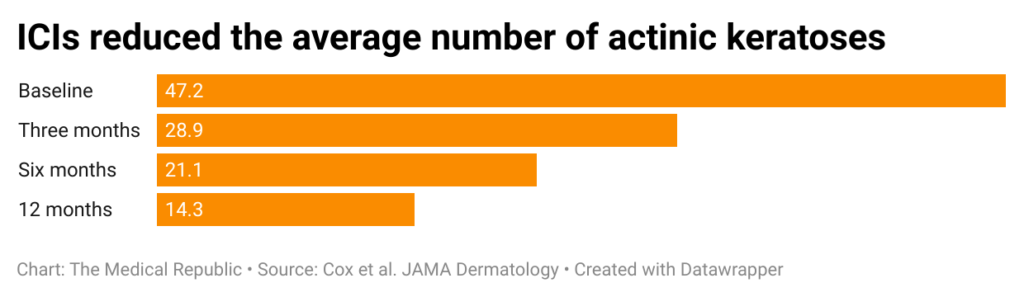

Eighty percent of patients displayed a reduction in the number of visible actinic keratoses at the three-month follow-up; this figure increased to 100% at the 12-month time point. The average patient displayed a 62% reduction in the number of visible actinic keratoses.

A greater proportion of patients who displayed at least a 65% reduction in the number of actinic keratoses were under the age of 65 compared to patients who displayed less than a 65% reduction (67% versus 10%). Similarly, a greater proportion of patients with a 65% or greater reduction in actinic keratoses self-reported a history of blistering sunburn compared to patients with a smaller reduction (100% versus 50%).

The researchers felt these associations would help one of the more challenging aspects of ICI therapy – figuring out which high-risk patients could reap the greatest benefit.

“UV radiation is considered the most influential environmental risk factor for both basal cell carcinoma and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, and a history of blistering sunburns is associated with both types,” they wrote.

“Similarly, older age is associated with a larger mutant clone size and a greater reduction in actinic keratoses. Thus, individuals with… a history of blistering sunburns may harbor more mutations, potentially increasing their immune targets for ICI therapy.”

Adverse events occurred in half of the participants, with maculopapular rash or pruritus the most commonly reported side effect associated with ICI treatment.

“Importantly, we observed that immune-related adverse events were not associated with greater reduction in clinical actinic keratoses count,” the researchers concluded.

Sunscreen, topical 5-flurouracil and retinoid tablets are three main approaches to stopping actinic keratoses from progressing to cSCCs, according to senior author Professor Kiarash Khosrotehrani, a dermatologist and clinical scientist from the University of Queensland – although the latter two are poorly tolerated by patients.

However, ICIs have also the potential to cause long-term, serious adverse events.

“Immunotherapies can have quite severe and lifelong toxicity. For example, if you stop using the creams, people get better. But immunotherapies are known for sometimes triggering your immune system and causing a long-term autoimmune disease. These cases are rare, but they exist,” Professor Khosrotehrani explained.

Professor Khosrotehrani and his collaborators are currently seeking funding to undertake a larger clinical trial to better explore the long-term risks and benefits, as well as the cost-effectiveness, of using ICIs as a preventative therapy.