Associate Professor Rosemary Nixon on identifying and treating one of the most common inflammatory skin conditions.

Contact dermatitis is one of the most common inflammatory skin conditions, with the prevalence estimated to be 8.2%1.

It also accounts for 70-90% of occupational skin disease (OSD)2. Contact dermatitis is caused by exposure to external substance(s) inducing an immune response resulting in skin inflammation3. Contact dermatitis classically starts on skin areas where the allergen has initially contacted the skin, and especially involves the hands and face4. Contact dermatitis can have a negative impact on quality of life (QOL), affecting relationships and employment5.

TYPES OF CONTACT DERMATITIS

Irritant contact dermatitis (ICD)

Irritant contact dermatitis is the most common form of contact dermatitis 6 and results from direct damage to skin by external agents and irritants that in turn activates the innate immune system. Irritant contact dermatitis is usually caused by the cumulative effect of weak irritants such as soap and water. Atopic individuals are more likely to experience irritant contact dermatitis 7.

Allergic contact dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis is a delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction to an allergen, and occurs only in previously sensitised individuals8. Re-exposure to the allergen results in memory T cells being recruited to the skin and eliciting an immunological reaction causing inflammation. Allergic contact dermatitis can present hours to days after allergen exposure.

Worldwide, nickel is the leading contact allergen with an estimated prevalence of contact allergy in 8-19% of adults1. It is said that there are 85,000 chemicals9 and more than 4900 contact allergens have been reported10. New allergens continue to emerge and differ slightly from country to country, depending on exposures.

In photoallergic contact dermatitis and photoirritant contact dermatitis, light exposure (primarily ultraviolet A) triggers the allergic or irritant reaction.

HOW IS CONTACT DERMATITIS DIAGNOSED?

Who gets contact dermatitis?

Females are more likely than males11 to be diagnosed with contact dermatitis, which is thought to be the result of increased occupational and domestic exposures to both irritants and allergens. Atopy is a recognised risk factor for irritant contact dermatitis 7 as a result of associated skin barrier impairment. Pre-existing irritant contact dermatitis facilitates the development of allergic contact dermatitis, because skin barrier impairment allows penetration of allergens.

High-risk occupations for irritant contact dermatitis are those involving wet work (see Table 1) which include healthcare workers, food service workers, metal workers, hairdressers and construction workers12.

| Wet work is defined as 13 |

| 1) Exposure of skin to liquid for more than two hours per day 2) Use of occlusive gloves for more than two hours per day or change of gloves more than 20 times per day 3) Frequent hand washing, more than 20 times per day, or use of hand disinfectants more than 20 times per day |

History

A comprehensive clinical history, especially of skin exposures, is important in making the diagnosis of contact dermatitis.

A patient’s history may reveal exposure to irritants or allergens that will guide further investigations and management. The timing, distribution of skin rash, clinical course, triggers, response to treatment and history of atopy are all important.

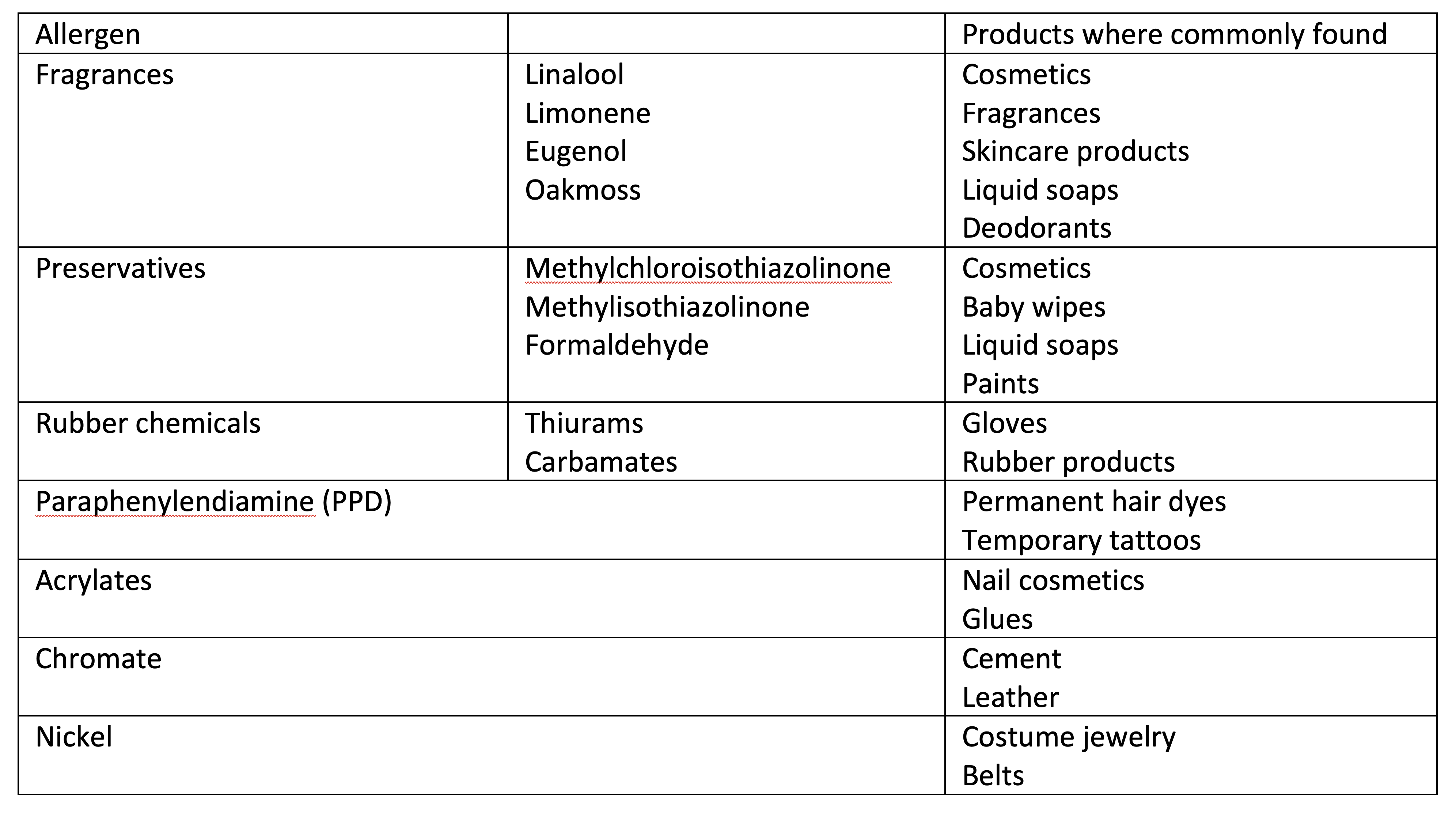

With the delay in the development of dermatitis following exposure to an allergen, it is often not possible to predict the causative allergen. Table 2 lists some of the most common allergens seen in our patch test clinic and where they are commonly found. It is important to ask about all exposures, including personal care products (hair dyes, shampoos, fragrances, essential oils, cosmetics, skin care products, nail treatments, hand washes, wipes), medicaments, recreational activities (crafts, gardening and carpentry)8, as well as occupational exposures and the use of personal protective equipment (rubber gloves and hand sanitisers, especially; Figure 1) .

Additionally, if a patient has recently been hospitalised, it is important to consider antiseptics (chlorhexidine), medical tapes and surgical glues such as Dermabond® (Figure 2).

As well as wet work, causes of skin irritation include soaps, solvents, oils, dust and physical factors such as heat, sweating and friction.

Irritant contact dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis may co-exist or complicate other skin conditions. The diagnosis of contact dermatitis should also be considered in individuals with atopic dermatitis who are unresponsive to treatment, who flare when stopping treatment or have an unusual distribution of disease4.

Occupational causes may be relevant, especially when the symptoms flare with work and improve when away from work. Taking a full occupational exposure history, including accessing relevant Safety Data Sheets, is important. Criteria for diagnosing occupational contact dermatitis have been established by Mathias14 with iterations of these seven criteria being included in the majority of occupational contact dermatitis guidelines.

Examination

The skin signs in contact dermatitis may be variable but typically begin at the site of contact with the offending agent. Acute CD is characterised by oedema, erythema and vesicles whereas chronic contact dermatitis is usually dry, scaly and hyperkeratotic, possibly with fissuring.

Allergic contact dermatitis typically extends outside the original area of contact with allergic contact dermatitis, tending to form vesicles or bullae in severe cases. Early signs of irritant contact dermatitis involving the hands include interdigital dermatitis (Figure 3), also referred to as the “sentinel” sign and often seen in occupations involving wet work15.

Distinguishing the type of contact dermatitis based on lesion morphology has been shown to be unreliable, hence it is difficult to reliably clinically differentiate irritant contact dermatitis from allergic contact dermatitis16.

Investigation

While some cases of allergic contact dermatitis are straightforward (such as reactions to nickel in costume jewelry or to fragrance in a deodorant), more complex cases, where the allergen is unclear, should be referred to a dermatologist for consideration of patch testing.

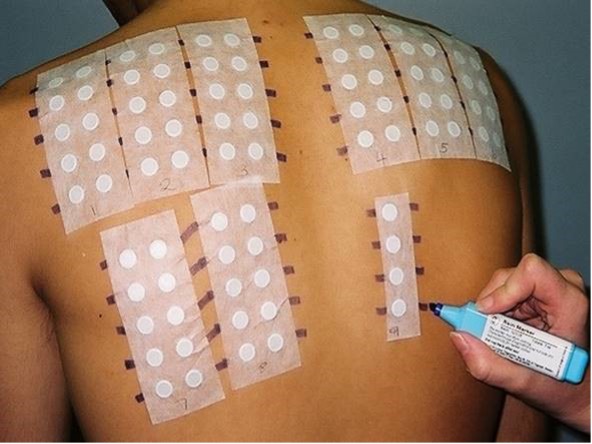

Patch testing is the gold-standard investigation of allergic contact dermatitis17 (Figure 4 and 5), whereas there is no routine diagnostic test for irritant contact dermatitis and it is usually a diagnosis of exclusion.

Patch testing differs from skin prick testing, which is used to evaluate immediate hypersensitivity or Type I allergic immune reactions. In Australia, patch testing is predominantly performed by dermatologists, not allergists, and requires expertise and practical experience.

While patch tests are routinely performed to a national allergen baseline series, featuring the most common and relevant allergens in a population18, additional series are tested based on the patient’s history and occupation (e.g. rubber, cosmetics, nurses’ and hairdressers’ products) and finally, patients’ own products are tested, with particular care taken to dilute them appropriately so as to not cause irritant reactions.

The presence of a positive patch test alone does not confirm the diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis, which also requires a history of exposure to the positive allergen and a compatible clinical course. The process of patch testing and making a diagnosis has been shown to have a positive impact on QOL, even in cases of negative patch test results19.

The use of spot tests can demonstrate exposures to allergens such as nickel, chromium and cobalt.

Skin biopsies are of limited value in differentiating the types of contact dermatitis and other forms of eczematous rashes but can be helpful in excluding other differential diagnoses.

TREATMENT

Prevention

It is important to reduce exposure to allergens, and this has occurred through legislation in some jurisdictions. Europe adopted limits on the amount of nickel in jewelry (August 1994)20 while legislation also has decreased the amount of allergenic chromate in cement (January 2005)21. It is important that manufacturers limit the use of allergens where possible.

Over decades, there have been many waves of allergic contact dermatitis to preservatives, most recently culminating in an epidemic of allergic contact dermatitis to the preservative methylisothiazolinone (MI) (Figure 6)22. Exposure to baby wipes and subsequently hand washes and shampoos were major causes of the epidemic, which was eventually halted by legislation reducing the allowed concentration of MI in leave-on and rinse-off products.

In a study of occupational ACD in Victorian healthcare workers in 2016, we found many cases of allergic contact dermatitis caused by chemicals in gloves and hand cleaners, which were impossible for the healthcare workers to avoid23.

Generally, the use of appropriate PPE is recommended in preventing contact dermatitis. In some occupational situations, this may be complex, as not all gloves protect against all allergens24.

Education regarding skin protection, use of appropriate PPE and skin care is the key to the prevention of contact dermatitis and has been shown to be effective in reducing the number of newly diagnosed occupational cases of irritant contact dermatitis25. Nevertheless, education needs to be repeated to be effective over time.

Management

The definitive treatment of contact dermatitis is making a diagnosis: the identification and avoidance of the underlying causes4both at home and in the workplace. Patient education is essential. Patients should be provided with information regarding their diagnosis, identified allergens and presumed irritants, and taught to check ingredient lists if appropriate.

For those with occupational contact dermatitis, the involvement of occupational health personnel together with employers may be required, especially if the individual needs time off work, or needs modified or alternative duties.

Regular application of emollients is advised to enhance skin barrier function26, in particular the use of lipid-rich emollients, which have been shown to improve healing in damaged skin in experimental studies27.

Hand Hygiene Australia recommends the use of alcohol-based hand rubs for healthcare workers with hand washing to be reserved for scenarios when hands are visibly soiled28. To minimise irritation when hand washing, the use of soap substitutes29is recommended.

Short-term use of topical corticosteroids is effective, but they inhibit the repair of the stratum corneum and, very occasionally, induce skin atrophy. In patients with a serious risk of adverse effects from topical steroids, the use of topical calcineurin inhibitors should be considered, given the similar efficacy to topical steroids30 especially in contact dermatitis affecting the face and neck31.

For cases of recalcitrant contact dermatitis, narrow band ultraviolet B treatment, psoralen combined with ultraviolet A light (PUVA) treatment or systemic treatment with immunomodulators (such as methotrexate, mycophenolate, ciclosporin or azathioprine) may be used32.

PROGNOSIS

The prognosis is dependent on being able to avoid the offending irritant or allergen, but the skin may take time to recover, and even when it appears normal, it may be easily irritated.

Risk factors for persistent occupational dermatitis are longer duration of hand dermatitis prior to diagnosis and atopy33.

Severe contact dermatitis is associated with a poor prognosis, despite advancements in prevention and treatment strategies. Some 10% of workers with occupational dermatitis develop persistent post-occupational dermatitis, where they fail to improve despite avoidance of the causative factors34.

Associate Professor Rosemary Nixon AM is qualified in both dermatology and occupational medicine and has been patch testing since 1987. Dr Kajal Patel was her research fellow at the Skin Health Institute in 2021.

REFERENCES

- Diepgen TL, Ofenloch RF, Bruze M, et al. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population in different European regions. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174(2):319-329.

- Cazzaniga S, Lecchi S, Bruze M, et al. Development of a clinical score system for the diagnosis of photoallergic contact dermatitis using a consensus process: item selection and reliability. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(7):1376-1381.

- Alinaghi F, Bennike NH, Egeberg A, Thyssen JP, Johansen JD. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80(2):77-85.

- Fonacier LS, Sher JM. Allergic contact dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;113(1):9-12.

- Kadyk DL, McCarter K, Achen F, Belsito DV. Quality of life in patients with allergic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(6):1037-1048.

- Bains SN, Nash P, Fonacier L. Irritant Contact Dermatitis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019;56(1):99-109.

- Meding B, Wrangsjo K, Jarvholm B. Fifteen-year follow-up of hand eczema: predictive factors. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124(5):893-897.

- Tan CH, Rasool S, Johnston GA. Contact dermatitis: allergic and irritant. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32(1):116-124.

- Gerlach C. New Toxic Substances Control Act: An End to the Wild West for Chemical Safety? In. Science in the news. Vol 2022. Harvard University2016.

- De Groot AC. Patch Testing. 4th ed. Wapserveen: acdegroot publishing; 2018.

- Thyssen JP, Johansen JD, Linneberg A, Menne T. The epidemiology of hand eczema in the general population–prevalence and main findings. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;62(2):75-87.

- Pesonen M, Jolanki R, Larese Filon F, et al. Patch test results of the European baseline series among patients with occupational contact dermatitis across Europe – analyses of the European Surveillance System on Contact Allergy network, 2002-2010. Contact Dermatitis. 2015;72(3):154-163.

- Menne T, Johansen JD, Sommerlund M, Veien NK, Danish Contact Dermatitis G. Hand eczema guidelines based on the Danish guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hand eczema. Contact Dermatitis. 2011;65(1):3-12.

- Mathias CG. Contact dermatitis and workers’ compensation: criteria for establishing occupational causation and aggravation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(5 Pt 1):842-848.

- Schwanitz HJ, Uter W. Interdigital dermatitis: sentinel skin damage in hairdressers. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142(5):1011-1012.

- Johansen JD, Hald M, Andersen BL, et al. Classification of hand eczema: clinical and aetiological types. Based on the guideline of the Danish Contact Dermatitis Group. Contact Dermatitis. 2011;65(1):13-21.

- Johansen JD, Aalto-Korte K, Agner T, et al. European Society of Contact Dermatitis guideline for diagnostic patch testing – recommendations on best practice. Contact Dermatitis. 2015;73(4):195-221.

- Toholka R, Wang YS, Tate B, et al. The first Australian Baseline Series: Recommendations for patch testing in suspected contact dermatitis. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56(2):107-115.

- Woo PN, Hay IC, Ormerod AD. An audit of the value of patch testing and its effect on quality of life. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;48(5):244-247.

- Delescluse J, Dinet Y. Nickel allergy in Europe: the new European legislation. Dermatology. 1994;189 Suppl 2:56-57.

- Commission E. Directive 2003/53/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 June 2033 amending for the 26th time Council Directive 76/769/EEC relating to restrictions on the marketing and use of certain dangerous substances and preparations (nonphenol, nonylphenol ethoxylate and cement). . In: Official Journal of the European Union 2003:178/124-178/128.

- Flury U, Palmer A, Nixon R. The methylisothiazolinone contact allergy epidemic in Australia. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;79(3):189-191.

- Higgins CL, Palmer AM, Cahill JL, Nixon RL. Occupational skin disease among Australian healthcare workers: a retrospective analysis from an occupational dermatology clinic, 1993-2014. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;75(4):213-222.

- Kersh AE, Helms S, de la Feld S. Glove-Related Allergic Contact Dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2018;29(1):13-21.

- Bregnhoj A, Menne T, Johansen JD, Sosted H. Prevention of hand eczema among Danish hairdressing apprentices: an intervention study. Occup Environ Med. 2012;69(5):310-316.

- Kasemsarn P, Bosco J, Nixon RL. The Role of the Skin Barrier in Occupational Skin Diseases. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2016;49:135-143.

- Held E, Agner T. Effect of moisturizers on skin susceptibility to irritants. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81(2):104-107.

- Australia HH. Alcohol-based handrubs https://www.hha.org.au/hand-hygiene/alcohol-based-handrubs. Accessed 19th January, 2022.

- Bourke J, Coulson I, English J, British Association of Dermatologists Therapy G, Audit S. Guidelines for the management of contact dermatitis: an update. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160(5):946-954.

- Katsarou A, Makris M, Papagiannaki K, Lagogianni E, Tagka A, Kalogeromitros D. Tacrolimus 0.1% vs mometasone furoate topical treatment in allergic contact hand eczema: a prospective randomized clinical study. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22(2):192-196.

- Ashcroft DM, Dimmock P, Garside R, Stein K, Williams HC. Efficacy and tolerability of topical pimecrolimus and tacrolimus in the treatment of atopic dermatitis: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2005;330(7490):516.

- English J, Aldridge R, Gawkrodger DJ, et al. Consensus statement on the management of chronic hand eczema. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34(7):761-769.

- Mahler V. Hand dermatitis–differential diagnoses, diagnostics, and treatment options. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14(1):7-26; quiz 27-28.

- Toholka R, Cahill J, Palmer A, Nixon R. Factors contributing to the development of occupational contact dermatitis and contact urticaria. Canberra: Safe Work Australia;2014.