Giving refunds to avoid trouble creates a dangerous precedent.

Increasingly when I see fellow healthcare professionals as patients, there is a sense of defeat and of demoralisation.

The work we do is devalued (they can Google it for free!), our qualifications are minimised (anyone can do it! “Should’ve gone to med school wink to make that kind of money!”) and people are learning firsthand that complaining is going to get them what they want thanks to fear of repercussions from regulators who happily investigate clearly vexatious complaints.

I had four vexatious complaints made to AHPRA last year, three of them from people whom I’d never met, who were not my patients, and two of whom complained anonymously about me based on my social media posts. One was a patient I fired after she referred to me as being “like a Nazi” and more.

All complaints were ultimately dismissed, as I knew they would be, but I still had to waste my own and my MDO’s time and energy. Each took months to resolve in my favour.

People have learned how to weaponise the regulator with baseless complaints, and sometimes using them to get refunds in the absence of error on the practitioner’s or practice’s part.

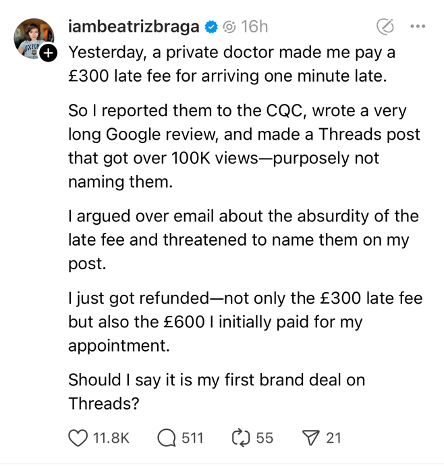

I was intrigued when someone from the UK recently posted this:

Further details revealed that she had arrived not one but 16 minutes late to her appointment with the doctor at a private clinic. This clinic gives 15 minutes’ leeway for being tardy. On arrival she was told her options: forfeit the £600 paid or pay another £300 and wait to be seen.

She chose to pay the additional fee to be seen (after waiting a further 20 minutes) and then after the fact, complained to someone and posted about it on social media, with the above resolution.

To her disappointment the vast majority of people were not in favour of her behaviour, noting she was significantly late and was not coerced into paying the extra fee; and that it was a private clinic, not run by the NHS, that could presumably charge what they wanted.

Note that AHPRA cannot usually regulate fees and charges by privately run clinics in Australia even if someone were to complain.

Nonetheless, she is now crowing about the fact that she got away with it and, by posting about it, normalising it and encouraging others to do likewise.

This is how it begins.

To be fair, I probably would have given a refund too if only to be able to discharge this person as a patient. But is that wise?

What I’m learning these days is that every “mistake” that can be weaponised is an opportunity to tighten my systems to avoid it happening again, and to place the responsibility back on to the patient where possible.

Patients who are regularly late to their appointments are asked if there is something we can help with to ensure they are on time (because I tend to run on time) as it is disruptive to everyone after them. Patients who argue about late cancellation fees and more are offered waiver of the fees in exchange for discharge from clinic.

To the person above, I did point out that while the fee did seem excessively punitive, she was in fact not one minute but 16 minutes late, and she had agreed to both paying the non-refundable fee upfront AND the additional fee in order to see the doctor on the day. She had consented, and then complained after the fact. Her only response: “It was a lot of money and I could have flown to Europe for that amount.”

That was hardly the point.

When I began studying medicine in the late 90s, I could not have imagined a time when we would be practising as defensively as we do now. Before covid I would not have imagined a time when patients would simply hop onto a two-to-three-minute phone call, having diagnosed themselves and determined what antibiotic or medication they needed for their self-limiting illness, and have it prescribed by the doctor at the other end with minimal questioning.

So it’s no surprise, I guess, that when large sums of money are involved, people feel angry, even if it was their error.

Some of my patients who are dentists and orthodontists tell me they are at a point where they simply refund fees paid as the price of terminating the therapeutic relationship with patients who turn out to be difficult.

This is a temptation for me every time a patient expects an excision without a scar or facial procedures with no bruising, or to have their non-normal results discussed in a free phone call.

(“Would you prefer we send you the copy of the results to take to a doctor of your choice if you don’t wish to pay for an appointment to discuss results?” I always ask first, and get verbal consent.)

Likewise when a patient expects a permanent cure for long-term skin disorders – acne, dermatitis, melasma – because their friend went to a non-doctor who offered them such a solution. (My response is usually “Maybe you should consult them for an opinion.”)

When a patient demands a refund from me because of a known complication with no error on my part, having given informed consent to a procedure – that’s where I draw the line.

A refund is not only a tacit admission of guilt. According to AHPRA, a refund is no obstacle to making a complaint (nor is an NDA). Not only is it dangerous, it won’t save you the hassle if the patient decides to complain anyway.

In an age of immediate gratification and quick fixes, we have lost sight of personal responsibility, accountability, the value of someone else’s time and what it means to be a patient – there is no patience, pun intended, in dealing with illness.

When as healthcare professionals, we cave and give in when it would be better for us as a profession to stand firm, we are creating a rod for our own collective backs.

Dr Imaan Joshi is a Sydney GP; she tweets @imaanjoshi.