Onerous new CPD requirements are now in place, but some dermatologists say there’s no evidence they have any value.

The new year ushered in significant changes to the way many medical professionals, including dermatologists, keep up to date with developments in their practice area.

And some dermatologists are not convinced there’s evidence that CPD ― at least, in its current format ― benefits either individual practitioners or the specialty more broadly.

The professional performance framework

The new CPD is by far the most important of the five “pillars” of the Medical Board of Australia’s Professional Performance Framework, which are designed to support doctors in “taking responsibility for their own performance, and it encourages the profession to raise professional standards”.

However, that first aim has rankled some doctors, and others are sceptical of its ability to do the latter. A second pillar concerns minimising risk, with the board proposing mandatory peer reviews and health checks for doctors at age 70 and every three years after.

The framework is being introduced progressively and not every area of medical practice is currently at the same stage. Some elements are already in place, or only require fine tuning, while others have involved significant planning, consultation and development.

What happened on 1 January 2023?

On the first day of the year, the Australasian College of Dermatologists (ACD) and all other accredited specialist medical colleges became “CPD homes”, accredited to administer CPD.

All doctors doing CPD programs will be able to meet updated CPD requirements.

Doctors who do not have a CPD home in 2023 can keep doing the same type of CPD that they are currently doing.

However, the board says they should keep their eyes peeled for any new CPD programs relevant to their scope of practice.

All doctors will need a CPD home by 2024, with several alternatives likely to have been established by then.

What do dermatologists need to do?

As of 1 January 2023, the new MBA requirements involve logging 50 hours of CPD per year, across three categories, and completing a professional development plan.

The focus of the changes is on regular performance feedback, collaboration with peers, self-reflection and reviewing patient outcomes. The 50 hours must be categorised according to type of activity, with dermatologists now needing to complete:

- 12.5 hours (25%) of hours recorded under educational activities

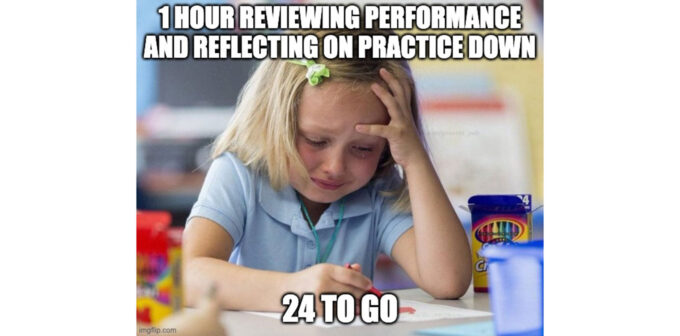

- 25 hours (50%) of hours recorded across reviewing performance and reflecting on practice and measuring and improving outcomes (with a minimum of five hours for each category)

- the remaining 25% (12.5 hours) distributed across any of the three types of CPD

“From the perspective of the regulator, the Medical Board of Australia, the new program expands the activities of the dermatologist to a more point-by-point compliance with the overarching idea of a CPD program,” says Associate Professor Stephen Shumack, a past president of the ACD.

“I think the negative side is that it’s become much more complicated, and it’s become more difficult ― both in the time and activities required ― for dermatologists to be able to comply with the program.

“I think that will cause some significant angst among the fellowship of the college, particularly as we near the end of the 12-month period,” he says.

“I suspect there’ll be some frantic calls about how to do X, Y or Z, particularly with categories that cover reviewing performance, reflecting on practice, and measuring and improving outcomes.”

Time for reflection

While medical professionals are accustomed to keeping up to date with developments in their practice area, the need to review performance and reflect on practice has not been received as well in all quarters. These activities, along with measuring and improving outcomes, make up at least half of the hours required under the new framework.

Associate Professor Kurt Gebauer, director of Fremantle Dermatology in Perth, is concerned about the CPD burden these requirements will likely add, but he’s not against the concepts per se.

“I wouldn’t say [there’s no value in reflection] because if you’re a decent dermatologist, you should be doing that all the time,” he says. “You should be challenging what you do.

“If somebody’s saying something at a conference, for example, you should be prepared to put your hand up to say, ‘Hang on, I don’t follow your train of argument. Can you put it another way?’”

The RACGP’s nation clinical lead for CPD, Professor David Wilkinson, is less concerned.

“I don’t think anybody needs to get over-anxious about the word ‘reflection’ ― it’s just thinking about how this applies to my practice and how I get better,” he says.

“I think the tougher challenge is measuring outcomes. What the board is getting at there is for those of us in clinical practice, can we quantify the impact we’re having? For example, if you’re looking after a group of patients with diabetes, how do you know what their level of diabetic control is? Instead of just managing each patient as they come in, gather a little bit of data.

“You could, for example, gather six or seven patients’ records, look through them, remind yourself of the guidelines and check to see how many have achieved the recommended outcomes. Then you could think about whether there’s anything you need to change in your practice based on that. That’s it ― that’s your measuring outcomes.”

“Most of us do that all the time,” Professor Wilkinson says, “but what the board wants the profession to do is to be a little bit more rigorous about it.”

An unpaid box-ticking exercise?

Professor Gebauer, who as a former head of CPD at the ACD brings more than a little experience to the debate.

He says he is concerned about the lack of evidence to justify CPD or its role in improving the quality of education.

“Back then, I can’t recall having found any information that CPD was of any value for doctors,” he says.

“And my understanding is that the system hasn’t changed. There is no documentary evidence that making people go through CPD really improves the quality of the practitioner, particularly for dermatology.

“There are so many things in medicine where we need to go back and do a rethink to ask why this system exists. What’s the purpose and are we actually achieving it? If someone said to me, ‘What is the purpose of CPD?’ I’d say, ‘I have no idea’.

“It certainly doesn’t seem to be satisfying if you’re looking at a document to show whether you’ve kept up to date.”

Professor Shumack is also concerned about the time burden.

“It’s certainly an onerous impost on dermatologists’ time, particularly when we’re already very busy, and particularly when there’s not a huge body of evidence to demonstrate the benefit to our patients of these sorts of activities,” he says.

The review and reflect requirements are primarily relevant to dermatologists who are isolated, either geographically or because they have minimal contact with peers, he says.

“I’m certainly not aware of any scientific evidence that these two categories have significant generalisability,” he says.

“And it’s not so relevant in dermatology in the sense that we’re a small college, so we’re talking 600 or 700 people.”

Either way, 2023 will be a significant year for CPD ― for dermatologists and thousands of other practitioners.

What they have to say at the end of the year will be enlightening.